We’re gonna need a bigger boat…

This post is a shark story.

It’s also a history story, a comedy of mass incompetence, and a tribute to the power of the human spirit.

That story is the sinking of the USS Indianapolis. The worst shark attack in human history.

For the audio version, listen to the What We Sea podcast episode:

The USS Indianapolis (known as the Indy to her crew) was a US Navy Portland class heavy cruiser that served as the flagship of the US fifth fleet during WW2. The USS Indy was 610 feet long, which is just taller than the Space Needle, and could travel at up to 32 knots. The USS Indy transported President Franklin D. Roosevelt three separate times and participated in the attack of the Japanese Island of Iwo Jima.

And then came the USS Indy’s last, top secret mission…transporting and delivering the materials to make the atomic bombs that were later dropped on Japan.

Fun coincidence. I went to high school in Richland, WA. If you’ve heard of the Hanford site, you may realize that’s where the plutonium was made for the atomic bombs. We were also called the “Bombers“, and our mascot was the mushroom cloud. THAT mushroom cloud. Enough outrage later and they changed it to a bomber plane. But considering we firebombed the fuck out of Tokyo is that really better?

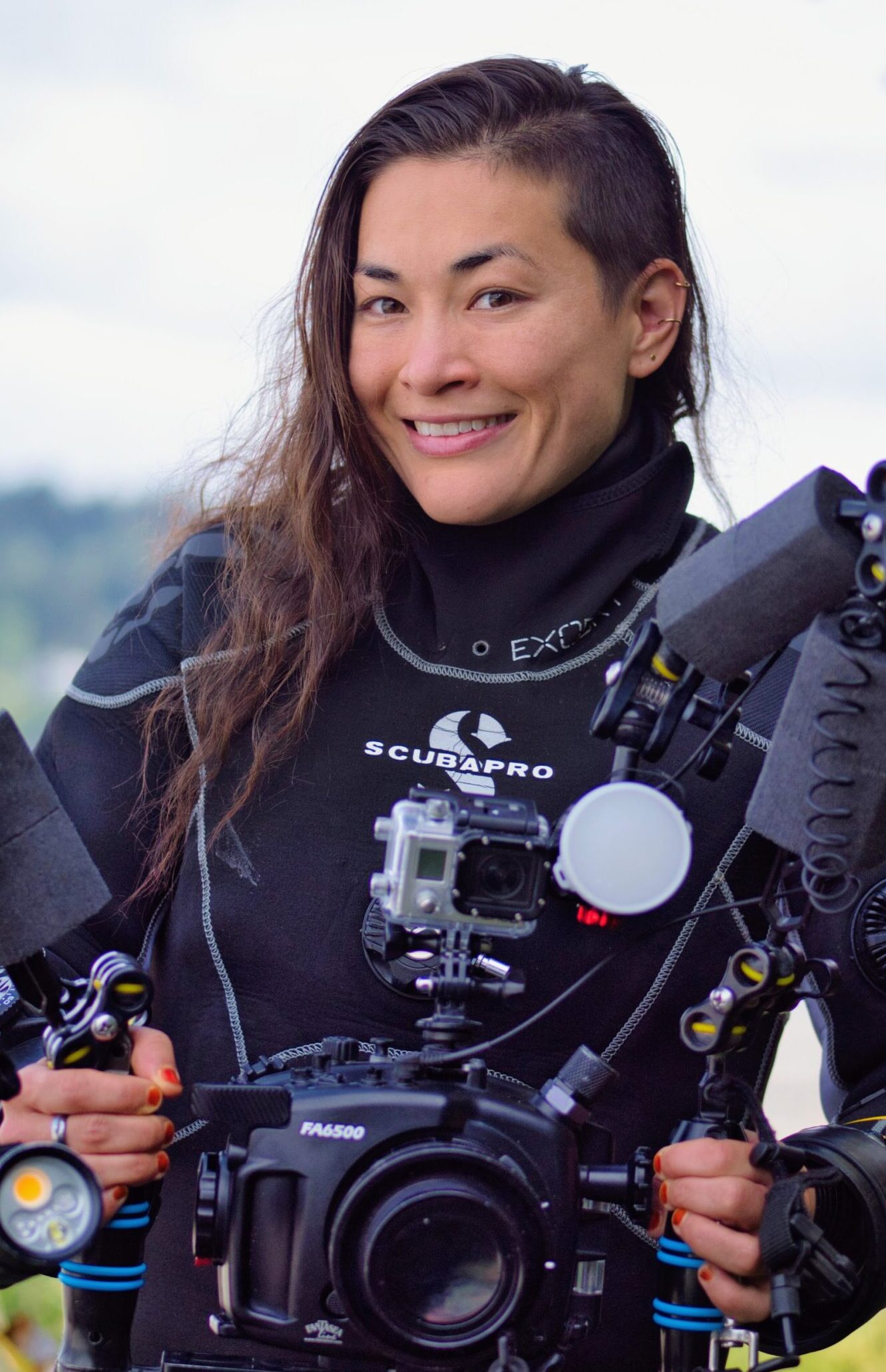

The Author questioning the nature of high school mascots and the complexity of the universe

After dropping off the big bang in Tinian, one of the islands in the Mariana Islands, the USS Indy was ordered to sail to the Leyte Gulf in the Philippines for training. The voyage was supposed to take 10 days.

The captain of the USS Indianapolis, Captain Charles McVay, asked for an escort for the journey. The Indianapolis didn’t have sonar, meaning they had no way to detect enemy submarines unless someone spotted one. With their eyeballs. In the middle of the open ocean.

Captain McVay was informed he didn’t need an escort. Military personnel believed that since the war was coming to an end and that Japanese forces were strained, the risk of an attack was minimal.

At least that’s what they said. In reality, just 4 days before the USS Indy sank, another ship, the USS Underhill, was torpedoed and sunk by a Japanese submarine. Military code breakers also knew that Japanese submarines were operating in the waters between Okinawa and the Philippines. In fact, they knew Japanese sub I-58 was traveling on essentially the same route as the USS Indy. No one told Captain McVay any of this. He was told things were fine and that an escort wasn’t available. Was an escort available you may ask? Yes. Yes it was.

But as far as Captain McVay was informed, it was completely safe to go alone. And with that, the USS Indianapolis set sail for the Philippines on July 26th 1945 .

On the night of July 29th at around 2300 the USS Indy was about halfway to its destination, slightly ahead of schedule. The weather was cloudy with limited visibility, so Captain McVay ordered the ship to cruise at 17 knots and cease zig zagging. Zig zagging is a military tactic meant to evade torpedo attacks from submarines. Captain McVay had been given discretion to zigzag if conditions allowed. The limited visibility meant zig zagging wasn’t advisable.

Earlier, we discussed a Japanese submarine traveling the same path as the Indy. On this night, this sub, captained by Commander Mochitsura Hashimoto, would spot the USS Indianapolis. Due to Commander Hashimoto’s later capture and interrogation by the US military, we have a timeline of the sinking from his point of view.

According to Commander Hashimoto, on the evening of July 29th around 1800 visibility was so low they couldn’t spot anything through the periscope. However, upon surfacing around 23:05 conditions had improved dramatically, allowing Hashimoto and his crew to spot the USS Indy and proceed to battle stations to begin an attack. Hashimoto ordered “Shooting Method Number Six”, which is an attack designed to be effective even if its target is zig zagging.

At this point, the Indy’s fate was sealed.

Just past midnight on July 30th, 1945 the first of two torpedoes struck the USS Indy instantly killing 300 sailors. It only took 12 minutes to sink. A ship the size of the Seattle Space Needle went from the initial hit, to listing, rolling on its starboard side, to completely sunk in only 12 minutes. Of the nearly 1200 sailors onboard, about 900 survived the initial explosion.

The USS Indy sank so fast that many sailors were unable to get to life rafts or grab proper provisions. This was made worse by the fact that the blasts took out Indy’s ability to send out a ship wide alert, which meant the order to abandon ship was given word of mouth only. It was impossible to be communicated ship-wide. Luckily, Chief Radio Electrician Leonard Woods managed to send out three S.O.S. signals in that time, giving his life in the process.

Sailors jumped, or stepped, into the ocean either with a life vest, or without anything. Sailors found themselves clinging to floater nets or taking life vests off of sailors who died from their injuries. Groups formed, some of about 30 sailors, some up to 300 or more. One report I found reported one survivor by himself on a raft and two others on a floater net. These groups separated from one another, becoming spread out over 25 miles. Captain McVay was in a group of about 30 survivors, luckily with life rafts. He believed he was the only group of survivors due to how separated the men were. The largest group of about 300 sailors only had life vests, and clung to each other for safety.

Despite this, morale was as good as it could have been. They believed the three S.O.S. calls plus the flares deployed by survivors in the life rafts meant they would be rescued soon. And besides, the USS Indy was due in Leyte in a few days. Surely someone would quickly notice and come to the rescue.

Except… It was only by accident the survivors of the USS Indy were found 4 days later on August 2, when a pilot noticed an oil slick and followed it to a group of survivors. The US Military had not realized the USS Indy had sunk.

How did this happen? How do you lose an entire ship, that is expected at its destination and that sent out three SOS signals before it was lost?

The simplest answer? A miserable comical cocktail of incompetence, negligence, and miscommunication.

Survivors who made it into life boats found and utilized flares to signal for assistance. They fired so many, a passing air force pilot who saw them described the scene as “naval action”. However, his report was dismissed as “if it was naval action, that the Navy knew about it.”

But what about the fact the ship was due in Leyte? Wouldn’t they notice the Indy didn’t arrive?

People noticed the USS Indianapolis failed to arrive… they just didn’t report it.

It was standard procedure during the war that to avoid clogging the airwaves, ships arrivals should not be reported due to an overwhelming amount of ships arriving at all times. Somehow that logic also led them to conclude that non arrivals should also not be reported. The pilot who was supposed to meet the Indy? Didn’t report it. The Port Authorities in Leyte who were expecting Indy’s arrival also didn’t report it missing. Some assumed it was late, or had gone to Manila, or been rerouted elsewhere.

And what about those three S.O.S. calls?

Funny story. One was ignored because the guy told his men not to bother him, another was drunk, and the third thought it was a trap by the Japanese.

Some background. Many of the reports and articles I found stated that the SOS’s were never successfully transmitted. Which does make sense given the electrical damage caused by the torpedoes. However I was reading through one of my sources, the book ” A Grave Misfortune: The USS Indianapolis Tragedy” by Richard A. Hulver. It’s an incredible resource and includes testimony from survivors, court transcripts, and a list of people who received letters of reprimand for the loss of the USS Indy. I noticed one of the names listed, Commodore Jacob H. Jacobson, wasn’t listed anywhere else except the index. All other names listed explained why they were reprimanded, mainly the Captain McVay and the officers stationed at the Port of Leyte who failed to report the Indy was missing. So I googled this missing name and found an article that stated Jacobson received one of the S.O.S’s… and ignored it because he was drunk. The officer who delivered the message to Jacobson noted the smell of alcohol. I found some articles that mentioned the other soldiers who received the S.O.S.’s, but the sources were a bit less reliable in my opinion. Feel free to check out my resources below to learn more!

And finally, what about the fact that the US intercepted a message sent by Captain Hashimoto (the dude that sank the Indy) in which he stated he sank a ship like the US Indy in the area the US Indy was?

This was dismissed as a trick by the Japanese to lure the US military into a trap. Literally the guy that sank the ship decides to humble brag and that’s not enough.

Needless to say, even before the sharks showed up, conditions for the survivors were harrowing. Yes, unlike the Titanic the survivors were stranded in the Pacific, meaning they didn’t freeze to death. However, being submerged for days at a time even in the warmer waters of the Pacific means men were severely chilled. And when the sun rose it was unbearably hot.

“You could barely keep your face out of the water…It was so hot we would pray for dark, and when it got dark we would pray for daylight, because it would get so cold, our teeth would chatter.”

Loel Dean Cox, survivor USS Indianapolis

The water was also covered in a slick layer of oil, which coated everyone. Many sailors accidentally swallowed this oil slicked water, causing them to vomit and accelerating the effects of dehydration. On top of that, the life jackets worn by the crew were made of a material called kapok, and weren’t meant to hold up for long periods of continuous use. Captain McVay even reported “after about 48 hours the wearer had sunk low enough in the water so that if his head fell forward he would drown”.

Men began to suffer from mass hallucinations, including one where a group of sailors became convinced the Indy was right below them and stocked with fresh milk. The men who dove down never resurfaced.

Sailors were dying of drowning, of dehydration, drinking salt water and exhaustion. One sailor, Captain Parke, died of exhaustion after attempting to keep other survivors from swimming away. Others simply gave up and slipped under the waves.

If that’s not horrible enough…that’s when the sharks arrived.

Let’s be clear, the sharks were already there. The survivors could see them swimming below. Sharks live in the ocean. While we remember this tragedy let’s not blame sharks for what happened or seek vengeance. Especially since this species is critically endangered and a key part of the ecosystem. You’re more likely to get bit by a fellow human than a shark while millions of sharks are murdered annually by humans. Also if some chucklefuck in a speedo came into my house with a giant camera and flashing strobes I’d wanna bite him too.

We as water loving creatures should be clear eyed that when we go into the water, we are entering sharks’ habitat and should take care and be respectful. Also, there are certain behaviors we can avoid as to not draw shark’s attention.

Sharks can be attracted by…

- Loud, irregular noises

- Blood

- Excessive splashing or thrashing.

All things that sorta happened when the Indy sank.

Now before we get into the feeding frenzy, let’s talk about the shark species suspected to the involved, the Oceanic White Tip Shark. Also maybe a tiger shark was involved but scientists suspect mainly Oceanic White Tips.

To understand why Oceanic White Tips are the main culprits, let’s start with what kinds of sharks are common in the Philippines. We then eliminate any sharks that aren’t oceanic. Remember, the ship sank on the way to Leyte nearly 200 miles off shore. This eliminates sharks like lemon sharks, grey sharks, and even bull sharks as all these prefer shallow coastal waters.

That leaves species like Mako, Great White, Hammerheads, Blue, Silky, Tiger, and Oceanic White Tips. Species like Makos, Blues, Silkies and Hammerheads tend to be more on the shy side. Great Whites, although can be seen in the Philippines, are pretty rare. And Tiger Sharks are thought to be a mostly coastal species, although they can travel into deeper waters. Survivor accounts don’t mention striped sharks, although this doesn’t necessarily prove there were zero Tiger Sharks.

With this information we can conclude the Oceanic White Tip Shark, a known aggressive surface dwelling species, is our top suspect.

We have a quote by Captain McVay. He wrote of his experience…

“We had a shark that adopted us apparently sometime in the early morning of Monday. We couldn’t get rid of him. The kids who were in rafts by themselves on this one raft were scared to death of this shark because he kept swimming underneath the raft. You could see his big dorsal fin and it was white, almost as white as a sheet of paper, apparently spent most of his time on the surface and this fin had bleached out so he didn’t blend in with the water at all.”

Captain Charles McVay

The attacks were brutal.

First they went for the dead. Then they attacked the living, drawn by the men’s bloody injuries and the kicking and thrashing. One article I read even reported the case of men opening a can of Spam only for the smell to ignite a feeding frenzy, forcing them to throw it away instead of risking more shark attacks.

How many sharks the groups of survivors encountered varied wildly. Survivor Giles McCoy reporting “hundreds” of sharks in the water under his group. Others like Captain Lewis Haynes reported he only saw one and tried to catch it and eat it.

For those that encountered sharks, the details are graphic. Harwin Twible had his group organize “shark watches” after noticing sharks would go after lone survivors. The shark watches were designed to keep people together and attempt to scare them off when the sharks got close. Dead seamen were cut loose and pushed away in the hopes the sharks would leave the living alone. Hitting the sharks and slapping the water seemed to work at times, but at others a motivated shark set on a target would not be deterred.

Another sailor, attempting to wake his friend, turned the body to reveal he had been eaten from the waist down.

At night, sailors would feel the sharks as they circled below, coming closer and closer to brush against their legs. Out of nowhere, someone would begin screaming, only for it to suddenly fall silent again as they were pulled under.

When help finally arrived, one of the pilots, Lieutenant Adrian Marks, decided to make a water landing despite the risks due to witnessing sharks feeding on the remains.

Even as soldiers were pulled from the water, the attacks on the living and the dead continued. A report from the rescue effort stated…

“About half of the bodies were shark-bitten, some to such to a degree that they more nearly resembled skeletons. From one to four sharks were in the immediate area of the ship at all times. At one time, two sharks were attacking a body not more than fifty yards from the ship, and continued to do so until driven off by rifle fire.“

Of the 900 men who went into the water, only 316 survived. The exact number of deaths due to sharks vs other causes is unknown. Estimates range from a few dozen to over 150.

Captain McVay survived the sinking, only to be court-martialed over his role in the sinking. The US Navy claimed McVay’s failure to zigzag was to blame, despite evidence to the contrary. Among this evidence was the testament of the captain of the Japanese submarine that sank the Indy, Commander Mochitsura Hashimoto. Hashimoto testified that his use of a 6 shot torpedo would have worked even if the ship were zigzagging. Regardless, McVay was convicted. The embarrassment of the trial, the guilt he felt over the tragedy of the sinking, and anger directed at McVay by families of sailors who had died on the Indy, lead to him taking his life in 1968.

Here’s where it gets hopeful. Captain Hashimoto, the captain of the sub that sank the USS Indy, retired after the war and became a Shinto priest. In 1990 he met with survivors of the USS Indy at Pearl Harbor where, through a translator, he apologized saying “’I came here to pray with you for your shipmates whose deaths I caused”. He was forgiven, and joined the survivors of the Indy in their journey to exonerate Captain McVay. Finally, in 2010, McVay was finally exonerated.

Today, the legacy of the USS Indianapolis lives on. The shipwreck of the USS Indianapolis was discovered in 2017, 3 miles below the surface. A memorial was build in 1995. The crew was honored in 2020 with the Congressional Gold Medal.

The legacy lives on through Quint’s monologue in JAWS, and the 2016 Film Men of Courage.

And the story lives through the survivors and the families of those touched by the tragedy. The story is more than a shark attack. It’s a story of brave men who faced both natural and human disasters, and came together in the end in forgiveness and a search for justice and truth.

Resources:

Out of the Depths by David Harnell

The Tragic Fate of the U.S.S. Indianapolis: The U.S. Navy’s Worst Disaster at Sea by Raymond Lech